It seems we can’t find what you’re looking for. Perhaps searching can help.

Geographic Imager

Geographic Imager

Process spatial imagery quickly with intuitive tools in Adobe Photoshop

®

®

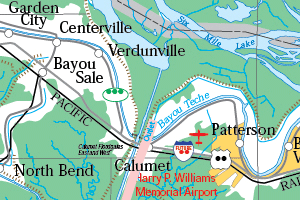

MAPublisher

When Map Quality Matters

Design beautiful maps with GIS data in MAPublisher for Adobe Illustrator

®

®

®